I recently read a book “Born to Be Wired” by John Malone, which describes the history of US internet cable industry - probably one of the most impressive (and underappreciated) infrastructure buildout since the railways. While the book was quite disappointing in writing, it got me thinking about an essay I wrote during studies on the automatisation of the telephone switchboard industry - a predecessor to Malone's internet cable business and similarly fascinating.

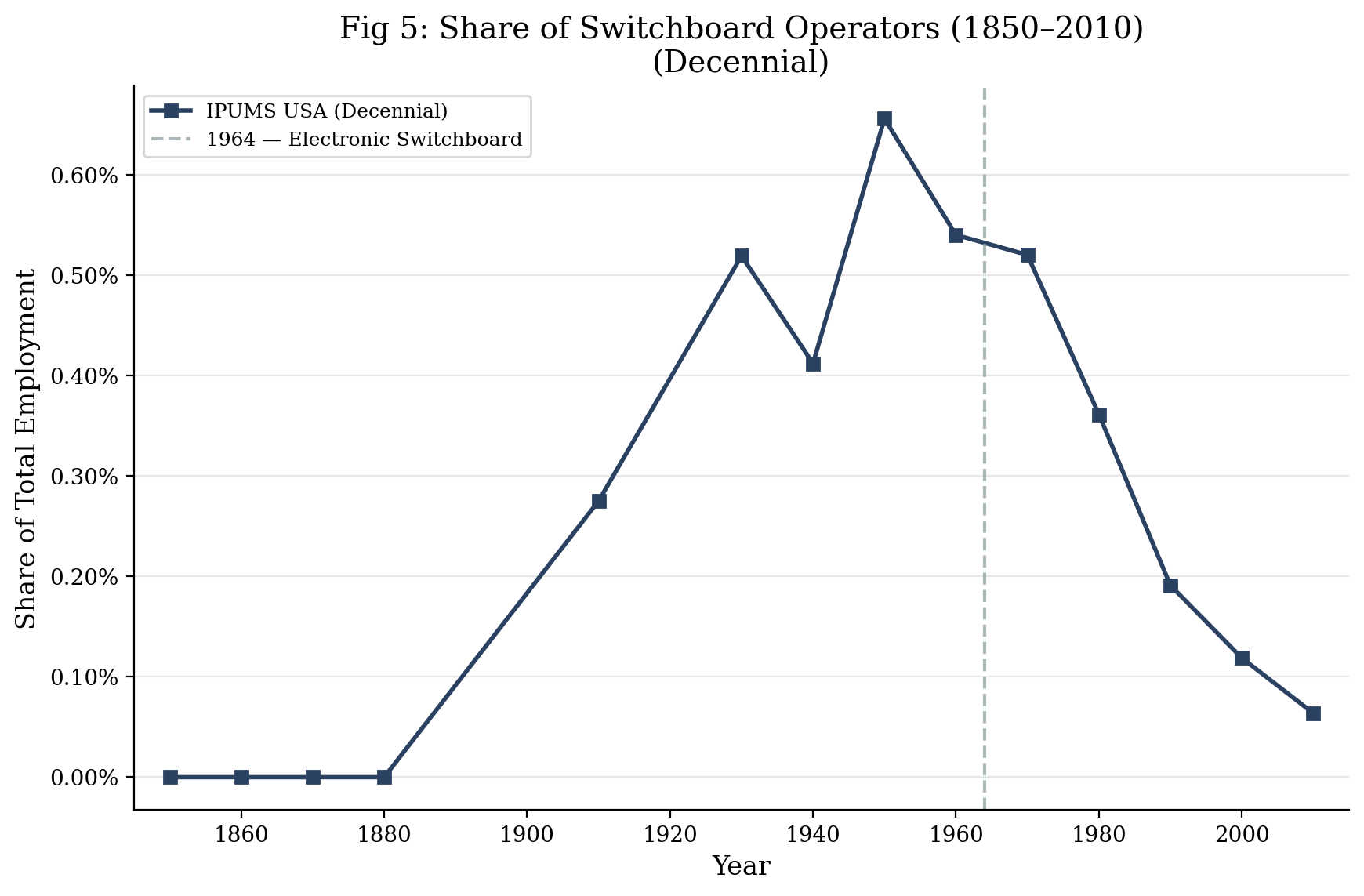

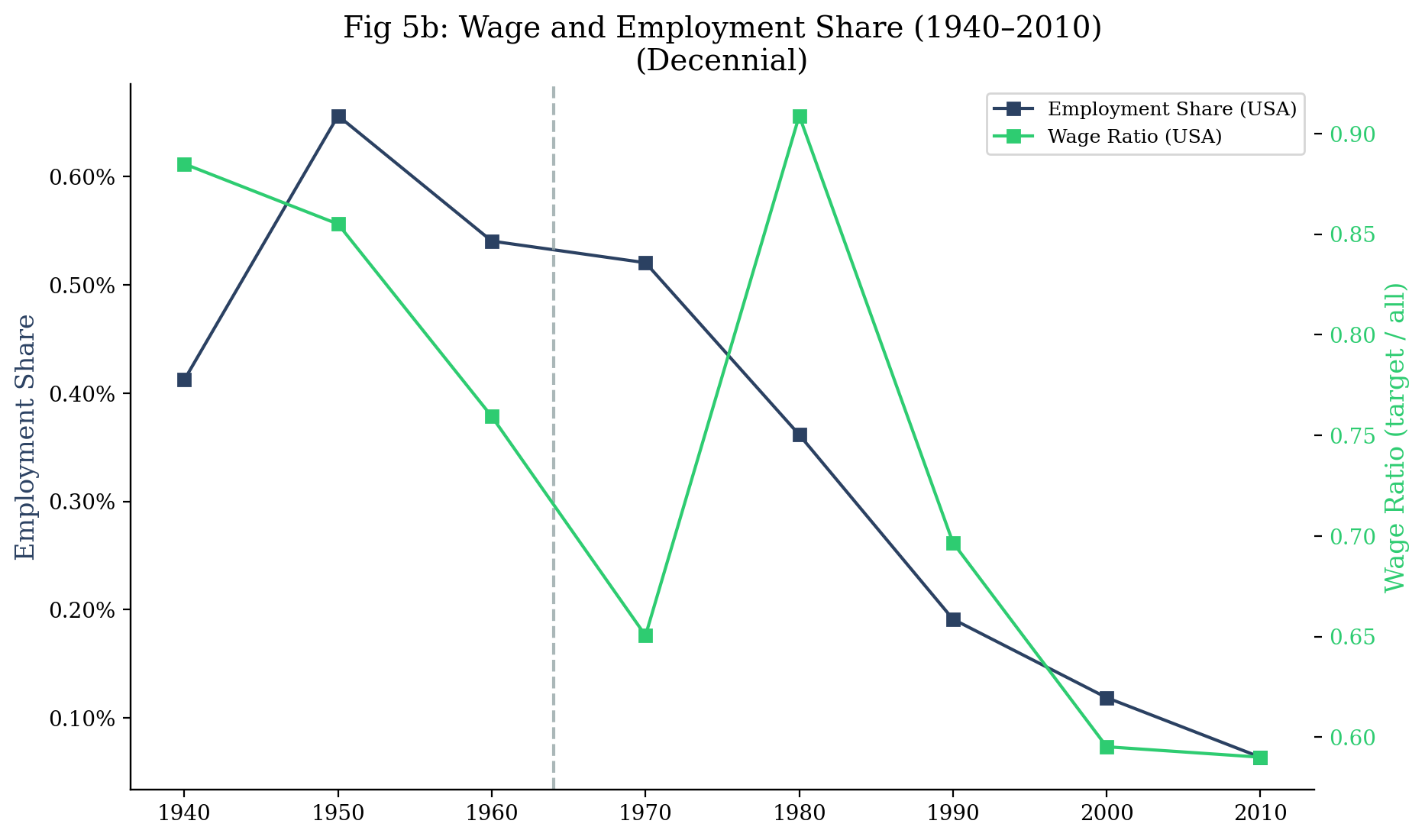

Currently, AI and it's speedup adoption in hardware robotics gives rise to lot's of speculation (both radically skeptical or overhyped) on what will happen to labour markets once 'robots replace humans' (AcemogluRestrepo2018, AghionJonesJones2017). I thought rereading the paper would be a good exercise to see if the same effects I studied could take place today. Inspired by Cavounidis et al., 2022, I demonstrate that, counter-intuitively, rapid replacement of manual operators by automatic switchboards has led to short-term increase in wages. When the automated switchboard was introduced, aspiring workers realised that the manual telephone operator job will be shortly obsolete meaning they did not train and apply to this industry. This meant the industry experienced a labour shortage leading to a wage premium the workers were able to exercise: an obselence rent. Firms were forced to pay that premium as they needed the manual labour just long enough to fully rollout the hardwarde and automatise the workflow.

Coming to today, everyone now expects major changes in hardware robotics but cannot yet pinpoint specific specialised jobs or industries that will be affected. Once that ‘unexpected’ innovation materialises in the coming years (or even months) e.g. a brand-new universal robotic arm in automative industry or automatic self-driving truck, it will be interesting to see what will happen to that industry from labour perspective. I would predict (or rather guess) that we could see similar effects as with switchboard industry, no newcomers want to become a specilised truck driver or metal welder as they know that the job will be shortly obsolete and therefore the industry will shortly flourish with wage increases before the jobs are 'made redundant'.

For ‘white collar’ jobs however, that is different story as the rate of technological adoption is far faster: it is much easier to replace an office analyst with an excel plug-in than rollout a full brand-new fleet of self-driving trucks. If I have a moment, I will try and extend the original economic model (by Cavounidis et al., 2022) and introduce a ‘speed of replacement’ and ‘capex’ constraints - it would be interesting to see if these would lead to, in theory, different dynamics between manual and non-manual jobs, where manual jobs can exercise an obselence-premium (just like the switchboard operators did) while office-jobs cannot - Could the XXIth centuryluddites come from ex-Accenture employees rather than the textiles workers?